It is H2 heading of the page.

It is H3 heading of the page.

It is H4 heading of the page

A rich text element can be used with static or dynamic content. For static content, just drop it into any page and begin editing. For dynamic content, add a rich text field to any collection and then connect a rich text element to that field in the settings panel. Voila!

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

- hello this is the list of page

- hello this is the list of page

Here is another list:

- hello this is ordered list of the page

- hello this is ordered list of the page

- hello this is ordered list of the page

- hello this is ordered list of the page

- hello this is ordered list of the page

Basic Life Support for Suspected Spinal Cord Injury: Essential Prehospital Guidelines

This article covers basic life support (BLS) for spinal cord injury, focusing on immediate care and scene safety. It guides airway protection, breathing and circulation management, cervical spine stabilization, and safe transport. Early recognition and proper care reduce secondary injury and improve survival and neurologic outcomes.

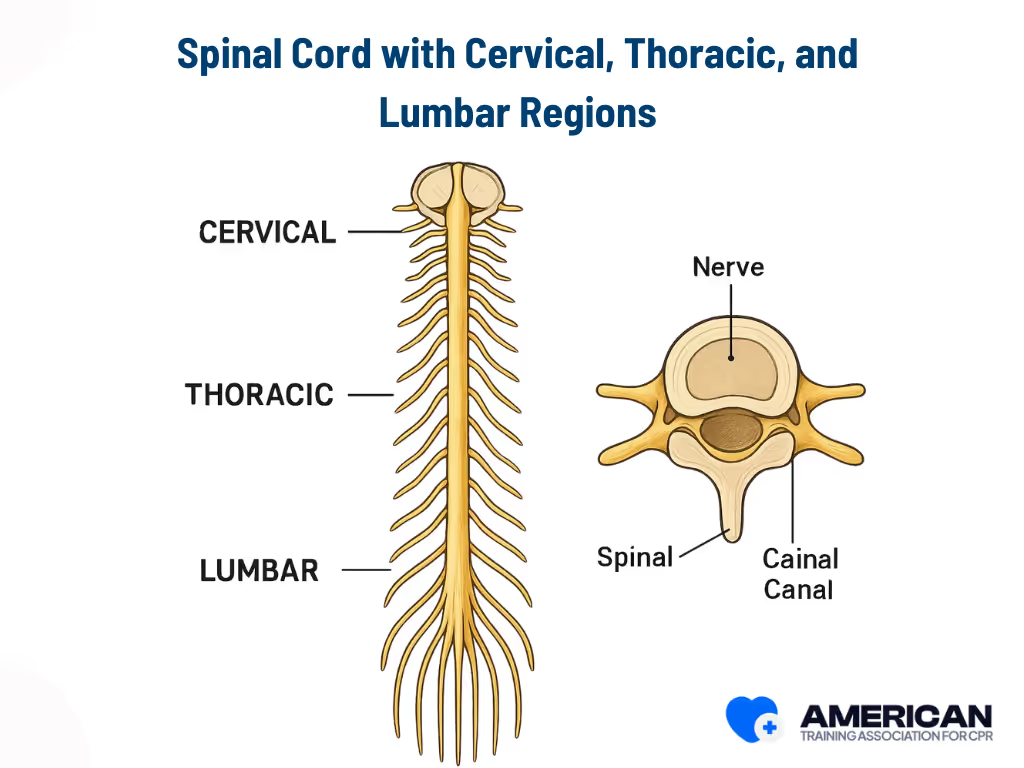

Understanding Spinal Cord Injuries

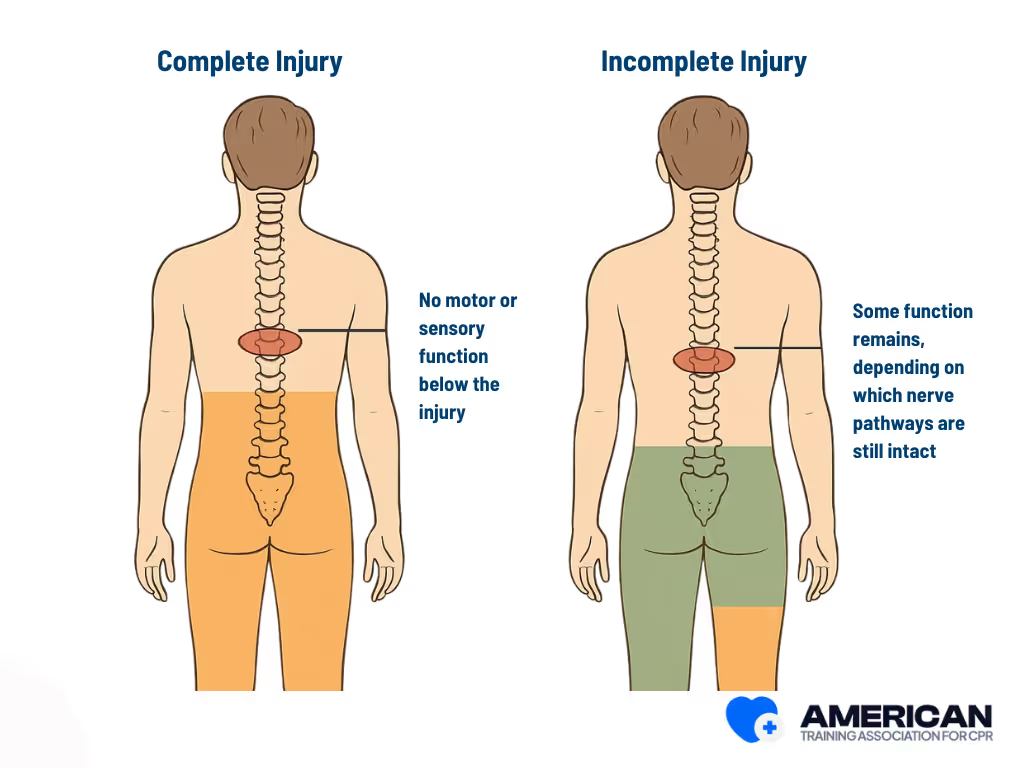

A spinal cord injury (SCI) disrupts the brain’s communication with the body, affecting movement, sensation, and automatic functions like breathing and heart rate. For anyone providing basic life support (BLS), understanding these effects is essential because they directly influence how you manage airway, breathing, and circulation while protecting the spine. There are 2 types of Injuries:

- Complete injury: No motor or sensory function below the injury.

- Incomplete injury: Some function remains, depending on which nerve pathways are still intact.

This distinction matters in BLS because the amount of motor and sensory loss affects airway protection, breathing effort, and how safely you can move or stabilize the patient.

What are the Common Causes of Spinal Cord Injury?

Spinal cord injuries result from external mechanical trauma, unintentional accidents, and internal medical conditions. Each one affects the spinal cord differently, but all can lead to serious neurological damage. Below are the primary categories and how they relate to SCI.

- Traumatic SCI: High-energy forces that directly damage the spine, such as motor vehicle collisions, firearm or stab wounds, contact sports impacts, and industrial crush injuries.

- Accident-related scenarios: Unintentional events like road traffic crashes, same-level or high falls, workplace incidents, and diving accidents that expose the spine to sudden impact or force.

- Medical-condition causes: Internal processes such as degenerative spine disease, spinal stenosis, spinal cord infarction, epidural hematoma, spinal epidural abscess, spinal tumors, and surgical or procedural complications that compress or injure the spinal cord.

- Mixed or multifactorial causes: A combination of internal and external factors, such as a fall causing a fracture in a spine already weakened by osteoporosis or metastatic bone disease.

Spinal cord injury arises mainly from trauma, accidents, and medical conditions, and understanding these cause categories helps responders anticipate clinical presentations and interpret early symptoms during assessment.

What are the Symptoms and Signs of SCI?

Spinal cord injuries commonly present with paralysis, loss of sensation, and breathing problems. These signs form a quick BLS checklist and help responders determine airway needs and when to apply strict spinal precautions.

- Motor loss: Weakness or paralysis in the limbs, either partial or complete. This affects positioning, airway access, and overall stability. Cervical injuries often impair all four limbs, while thoracic injuries usually affect only the legs.

- Sensory deficits: Numbness or reduced response to touch or temperature. Sensory loss helps localize the injury and may hide pain cues that normally guide safe handling during BLS.

- Breathing difficulty: Shallow breathing, reduced effort, or respiratory arrest—especially in injuries at C3–C5 where diaphragm control is affected. This immediately changes airway and ventilation priorities.

- Autonomic changes: Abnormal heart rate, low blood pressure, or warm, flushed skin. High cervical and thoracic injuries may trigger neurogenic shock, requiring close monitoring during BLS.

- Spinal tenderness: Localized pain, deformity, or step-offs along the spine. Even without other symptoms, tenderness alone is a red flag for possible spinal instability.

Together, these findings create the overall clinical picture of SCI symptoms, helping responders gauge urgency, predict airway and breathing risks, and maintain proper spinal precautions during basic life support. Recognizing these patterns early ensures safer handling and more effective prehospital care.

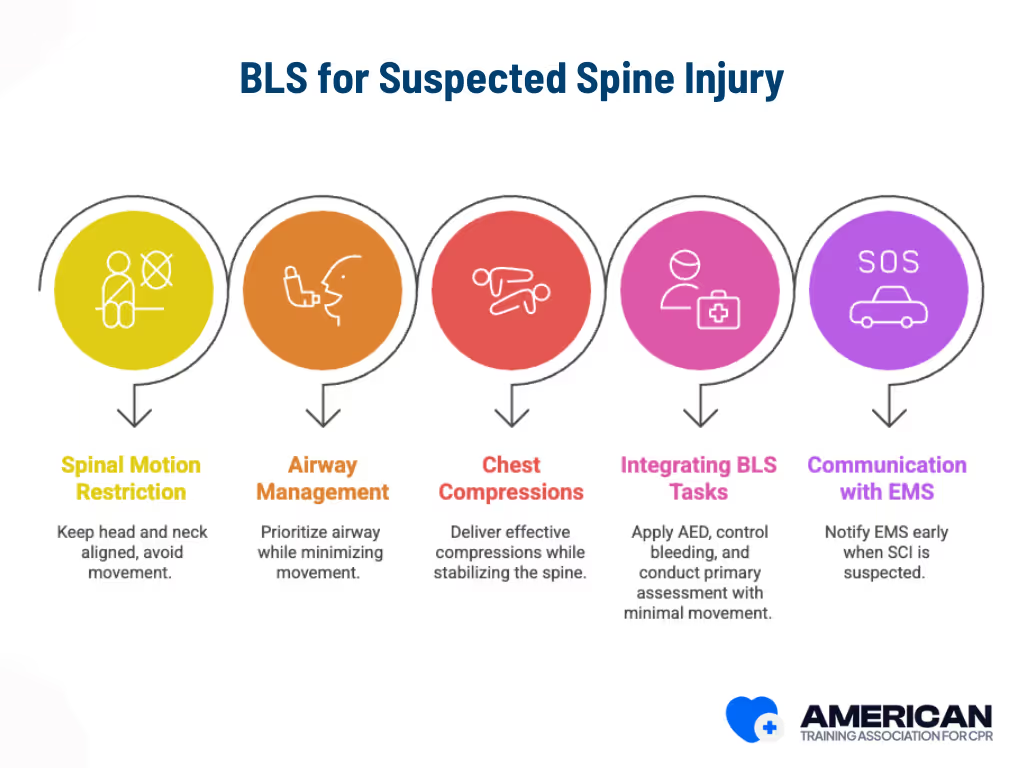

What Are the Special Considerations in BLS for SCI Patients?

Basic life support for spinal cord injury (SCI) patients must balance immediate life-saving care with the need to prevent further spinal damage. The focus is on spinal motion restriction, modified airway management, careful chest compressions, and clear coordination with EMS. Key considerations are:

- Spinal motion restriction: Keep the head and neck in neutral alignment. Avoid flexion, extension, and rotation. Maintain manual inline stabilization until advanced providers take over or the patient is secured to a spinal device.

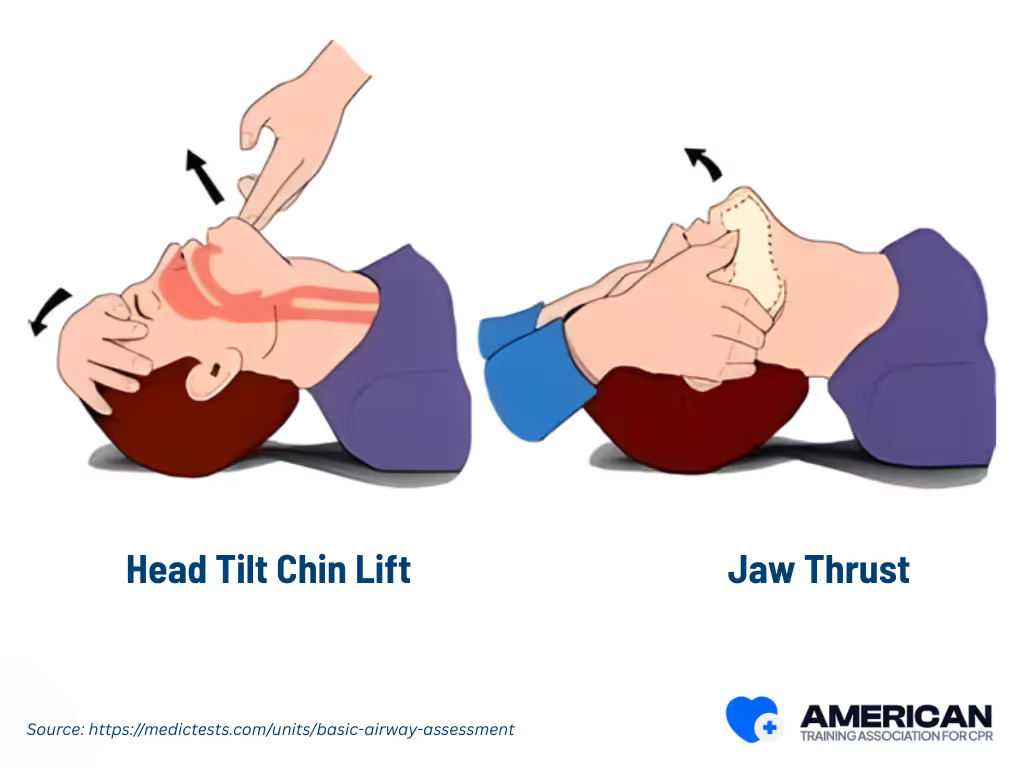

- Airway management: Airway comes first, but movement must be minimized. Use a jaw-thrust instead of head tilt–chin lift, suction carefully, and maintain inline stabilization during bag-mask ventilation. Use a second rescuer when possible.

- Chest compressions: Deliver strong, effective compressions while keeping the spine stable. The compressor should work from the patient’s side, while another rescuer provides manual inline stabilization. Avoid unnecessary repositioning or log rolls.

- Integrating other BLS tasks: Apply the AED, control bleeding, and conduct the primary assessment with minimal movement. Life-threatening issues, massive hemorrhage or airway compromise, still take priority, even if limited movement is unavoidable.

- Communication with EMS: Notify EMS early when SCI is suspected. Share mechanism of injury, interventions done, and current spinal precautions. Scene layout and available equipment, rigid collars, spine boards, scoop stretchers, or vacuum mattresses, guide how precautions are applied.

Rescuers must maintain spinal precautions, adapt airway and circulation support to limit movement, and coordinate closely with EMS. These principles set the stage for the upcoming Primary Assessment for Spinal Cord Injury Patients, where each step is applied in sequence.

What Is the Primary Assessment for Spinal Cord Injury Patients?

The primary assessment for spinal cord injury (SCI) patients is a rapid sequence that identifies life-threatening conditions while maintaining spinal immobilization. It prioritizes airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) without compromising spinal alignment.

The steps below follow the adjusted ABCs for SCI and must be performed with strict spinal protection. The anchor text primary assessment BLS SCI appears in Step 3 as requested.

- Check responsiveness: Assess consciousness using verbal cues or a shoulder or sternal tap without moving the neck. If unresponsive, assume SCI and activate EMS. Use only stimuli that do not cause cervical movement.

- Activate EMS immediately: Provide dispatch with key details such as suspected spinal trauma, mechanism of injury, responsiveness, and breathing status. One rescuer maintains manual inline stabilization while another makes the call.

- Open airway safely: Use a jaw-thrust while keeping the head in neutral alignment. One rescuer provides manual inline stabilization while the other performs the maneuver. Avoid head tilt chin lift unless absolutely necessary. (Anchor text: primary assessment BLS SCI.)

- Assess breathing: Observe chest rise, feel for airflow, and listen for breath sounds without moving the head or neck. If breathing is inadequate, start two-person bag-mask ventilation with inline stabilization and high-flow oxygen when available.

- Circulation and hemorrhage control: Check a central pulse and look for severe bleeding. Control hemorrhage with direct pressure, dressings, or a tourniquet as needed. Treat life-threatening bleeding immediately while maintaining spinal alignment.

- Rapid secondary cues: Look for signs that may modify initial care such as paradoxical chest movement, unequal chest expansion, spinal deformity, or new neurological deficits. These quick checks guide immediate decisions and should not delay lifesaving actions.

This sequence forms the core primary assessment for SCI patients. Every step balances urgent airway breathing circulation management with strict spinal protection. The next section will cover specific airway techniques for patients with suspected spinal injury.

CPR and FIRST AID

Certification

What Is the Secondary Assessment for SCI Patients?

The secondary assessment for spinal cord injury (SCI) patients is a head-to-toe examination that follows the primary survey. It identifies occult injuries, tracks neurological changes, and guides ongoing BLS decisions and spinal immobilization strategies.

This assessment supplements the primary survey by providing details that influence spinal alignment, airway management, ventilation, circulation, and movement restrictions. Key areas include wounds, fractures, bleeding, and changes in neurological status. Checklist for secondary assessment:

- Inspect fully: Examine the patient systematically from scalp to soles while maintaining rigid spinal stabilization. Look for lacerations, deformities, open wounds, active bleeding, burns, and limb alignment issues. Remove clothing carefully and palpate the spine gently within inline stabilization limits.

- Reassess neurology: Check level of consciousness, pupil response, motor function in key muscle groups, and sensory function in dermatomes. Document any changes from the initial exam. Use reproducible standards such as International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI to track serial changes.

- Monitor vitals: Trend pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. Watch for neurogenic shock—hypotension with bradycardia, hypoxia, or circulatory collapse—and communicate concerns for advanced interventions.

- Look for injuries: Identify thoracic, abdominal, pelvic, or extremity injuries. Control bleeding with direct pressure or tourniquet while preserving spinal alignment. Life-threatening hemorrhage may temporarily take priority.

- Correlate mechanism: Link the cause of injury (e.g., high-speed collision, fall, diving incident) with observed injuries. High-risk mechanisms increase suspicion for spinal involvement and help guide immobilization or splinting choices.

- Record findings: Document all secondary assessment results, changes since the primary survey, and interventions performed. Include vital signs, neurological scores, immobilization devices, and hemorrhage control measures. Prepare this information for EMS handover.

Continuous monitoring and documentation ensure safe ongoing resuscitation, spinal protection, and informed airway management, which will be addressed in the next section.

How Should the Airway Be Managed in Suspected Spinal Cord Injury?

Airway management in patients with suspected spinal cord injury (SCI) secures breathing while protecting the cervical spine. The key principle is neutral cervical alignment and minimal neck motion.

Why airway management differs in SCI?

Airway care must balance ventilation and oxygenation with spinal protection. Cervical fractures at C4–C6 are particularly vulnerable, and improper maneuvers can worsen the injury or convert an incomplete lesion into a complete one. Airway interventions are urgent if obstruction, hypoventilation, or low oxygenation persists after initial ABC measures.

- Head-tilt maneuver: Moves occiput and cervical vertebrae, causing extension. Safe for patients without suspected cervical injury.

- Jaw-thrust maneuver: Moves mandible with minimal cervical extension, preferred for suspected SCI. May be limited by facial trauma or trismus.

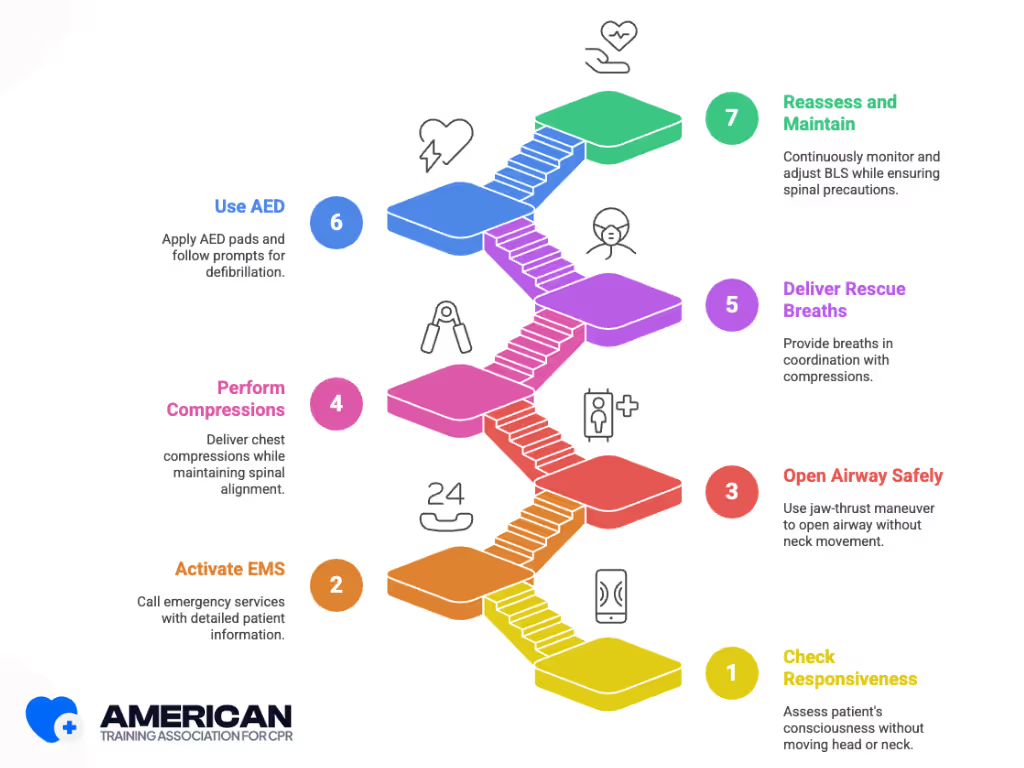

Step-by-Step BLS for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Spinal Cord Injury

Providing basic life support (BLS) to someone with a suspected or confirmed spinal cord injury requires careful attention. While airway, breathing, and circulation remain top priorities, protecting the spinal column is essential to prevent further injury. Every action should balance immediate survival with long-term neurologic outcomes.

1. Check Responsiveness Safely

The first step is to assess the patient’s responsiveness. Speak loudly and gently tap a shoulder or sternum, avoiding any head or neck movement. Watch for purposeful movements, chest rise, or eye opening, as these subtle signs indicate consciousness without risking spinal injury. How the patient responds determines the next steps and guides the level of spinal precautions required.

2. Activate Emergency Medical Services

If a spinal cord injury is suspected, call emergency medical services immediately. One rescuer should maintain head and neck stabilization while another communicates clearly with dispatch. Include details such as the patient’s age, location, suspected spinal injury, mechanism of injury, and current breathing and circulation status. Rapid notification ensures the arrival of trained personnel and appropriate equipment for spinal protection.

3. Open the Airway Safely

Airway management must secure breathing without compromising spinal alignment. The jaw-thrust maneuver is preferred because it opens the airway without moving the neck. Only use a head-tilt maneuver if the jaw-thrust is ineffective and cervical stability is not a concern. One rescuer maintains manual in-line stabilization of the head while another provides ventilation using a bag-valve-mask or pocket mask. Coordination is critical to provide adequate oxygenation while protecting the spine.

4. Perform Chest Compressions

Chest compressions should be done while keeping the patient’s torso aligned. Place hands at the center of the sternum and compress at a rate of 100–120 per minute to a depth of 5–6 centimeters for adults, allowing full chest recoil. A teammate should stabilize the patient’s head and neck whenever possible. Even with lower thoracic injuries, neck stabilization remains important. Minimizing rotation and flexion during compressions helps protect the spinal cord while maintaining circulation.

5. Deliver Rescue Breaths

Rescue breaths are given in coordination with compressions and the selected airway technique. Deliver each breath over one second and watch for visible chest rise to ensure effective ventilation. Use barrier devices or a bag-valve-mask with a two-rescuer technique when available. Adjust tidal volume and ventilation frequency to avoid excessive chest rise or unintended neck extension, preserving cervical alignment while ensuring adequate oxygenation.

6. Use an Automated External Defibrillator (AED)

After airway and circulation steps, apply an AED if available. Standard pad placement is anterior-lateral, but if spinal immobilization devices are present, adjust placement to avoid direct contact with equipment while maintaining at least a few centimeters distance. Follow the AED prompts while ensuring the patient remains stable, and minimize any movement to protect the spinal column.

7. Reassess and Maintain Spinal Precautions

Throughout the process, continuously reassess pulse, breathing, and responsiveness while ensuring spinal precautions remain effective. Coordinate rescuer changes so one person always maintains head and neck alignment while another performs compressions. Each reassessment informs ongoing BLS actions, helping preserve neurologic function and guiding interventions until advanced medical care arrives.

Preventing Secondary Injury During BLS

Preventing secondary spinal cord injury is a critical consideration during basic life support (BLS). Improper handling, uncontrolled movement, or unsafe airway and circulation interventions can worsen an existing spinal injury. Rescuers must carefully balance lifesaving interventions with spinal protection to reduce additional neurological harm.

- Core principles: Minimize spinal movement, maintain manual inline cervical stabilization, and prioritize airway and circulation while reducing additional cord injury.

- Scene and patient assessment: Identify high-risk mechanisms (falls, collisions, axial loads), assess consciousness and breathing, and note neurological deficits, pain, or deformity to guide precautions.

- Manual inline stabilization: Place hands on mastoids and jaw to maintain neutral alignment; avoid head tilt; one rescuer stabilizes while others perform airway or compressions.

- Safe movement techniques: Use log roll or lateral transfer only when needed; coordinate 3+ rescuers with verbal count; minimize interruptions to chest compressions.

- Stabilization aids: Use cervical collars, head blocks, stretcher straps, or improvised supports like rolled towels to limit motion while BLS continues.

- Chest compressions and airway adjustments: Keep compressions on the lower sternum, arms locked, 100–120/min, 5–6 cm depth; use jaw-thrust without head tilt for ventilations to protect the cervical spine.

- Team roles and communication: Assign head stabilization, airway, compressions, and scene management; use short commands to coordinate movements safely.

- Life-saving overrides: In cases of airway obstruction, absent breathing, or circulatory arrest, perform interventions immediately while minimizing spinal motion; document any deviations.

Coordinated precautions, handling techniques, and team roles reduce risk of further spinal injury during BLS, with special adaptations for high cervical injuries.

How ATAC Prepares Learners for Suspected Spinal Cord Injuries?

ATAC prepares learners for managing suspected spinal cord injuries through its online BLS certification program by focusing on cognitive understanding, scenario-based decision-making, and safe adaptation of BLS techniques for spinal precautions. The curriculum teaches learners to recognize injury mechanisms, prioritize airway and circulation interventions while protecting the spine, and make informed decisions during emergency situations. Interactive online scenarios and knowledge assessments reinforce procedural comprehension and critical thinking, ensuring learners can respond effectively and confidently to spinal cord injury emergencies without requiring in-person practice.

What Are the Benefits of BLS Certification for Spinal Cord Injury Emergencies?

BLS certification equips responders to manage spinal cord injury emergencies effectively by combining knowledge, practical guidance, and decision-making strategies. Key benefits include:

- Faster response times: Recognize spinal cord involvement quickly and prioritize interventions to reduce delays.

- Safe patient handling: Apply spinal motion restriction techniques to prevent secondary injury during airway management and chest compressions.

- Increased confidence: Scenario-based exercises build calm, decisive action in high-stress situations.

- Improved team coordination: Use standardized communication and handover protocols to relay critical patient information accurately to EMS and hospital teams.

Together, these skills enhance prehospital care, safeguard spinal integrity, and prepare responders to act effectively in real-world spinal cord injury emergencies.

CPR and FIRST AID

Certification

How do I start chest compressions if I suspect a spinal cord injury?

Start compressions immediately while maintaining manual inline stabilization of the head and neck. Deliver 100–120 compressions per minute at a depth of 5–6 cm for adults. Do not delay compressions to apply a cervical collar.

How should I open the airway if I suspect spinal cord injury?

Use a jaw thrust without head tilt. Maintain inline stabilization. If the patient is unresponsive and lacks a gag reflex, an oropharyngeal airway can assist ventilation. Bag‑valve‑mask ventilation with two rescuers is preferred.

What immediate steps prevent secondary spinal injury during BLS?

Maintain manual inline stabilization, limit torso rotation, avoid unnecessary spinal movement, and secure the head before moving the patient. Use a log roll with two rescuers if turning is required.

What modifications are needed for suspected high cervical injuries?

Recognize flaccid paralysis, absent respirations, or bradycardia. Prioritize airway patency with jaw thrust, prepare for assisted ventilation, avoid cervical extension, and continue high-quality chest compressions.

How long should spinal precautions be maintained during BLS?

Maintain spinal precautions throughout BLS and until advanced care is available. Exceptions are allowed only if immediate lifesaving interventions outweigh the spinal risk. Coordinate with additional rescuers during airway or extrication procedures.

Do AED procedures change for patients with suspected spinal cord injury?

No. Use standard AED application and rhythm analysis. Place pads in standard positions, avoid implanted devices, and limit interruptions to compressions. Avoid unnecessary patient movement that could worsen spinal injury.

What equipment is recommended for out-of-hospital spinal immobilization?

Use long backboards, spinal boards, vacuum splints, or Ferno Scoop Stretchers for prehospital cervical immobilization. Head immobilization techniques and manual in-line stabilization reduce cervical spine motion during transfers and air transport. EMS providers should assess for pressure injuries and reposition padding on support surfaces to minimize risk.

How can I prevent pressure injuries during prolonged BLS or transport?

Use full-body vacuum splints, inflatable bean bag boards, and adjust padding on support surfaces to reduce pressure on occiput and sacrum. Regularly check for pressure necrosis, pressure sores, or metabolic/electrolyte derangements that may compromise pre-hospital care.

How should responders handle patients from motor vehicle accidents or high-velocity sports injuries?

For trauma victims like ice hockey players, American football, or helmeted football athletes, follow pre-hospital care protocols: maintain rigid backboards, minimize range of motion, and stabilize the vertebral column, including the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. Radiographic evaluation and assessment of motor and sensory function guide safe transport.

CPR and FIRST AID

Certification

Real Stories from Our BLS Certified Participants